A retinal surgeon’s lawsuit questions the impact of modern capitalism on healthcare.

A corporate surge is sweeping across the medical profession, fueled by private equity’s expanding presence in healthcare. And with a recent whistleblower lawsuit filed against a major eye clinic in Arizona, the spotlight on the debate over the benefits and risks of this trend has taken center stage in patient safety in eye care.

On February 3, 2025, Dr. Charles Mayron (USA), a board-certified retina specialist, filed a lawsuit against Southwestern Eye Center (SEC) and its parent company, American Vision Partners (AVP), alleging wrongful termination in retaliation after raising concerns about patient safety. His complaint details the allegations: missed diagnoses leading to vision loss, staff unequipped to follow basic safety protocols, and key emails mysteriously deleted.1

READ MORE: When the Ball Drops on Sick Eyes: Patients Go Blind After Alleged Optometrist Misconduct

The temperature surrounding the debate over private equity in healthcare couldn’t be higher. The recent in-broad-daylight shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson sent shockwaves through American society and beyond, fuelling growing tensions surrounding corporate healthcare.

As allegations of profit-driven strategies shaping clinical operations swirl, public outrage is at a boiling point over the impact2 on both doctors and patients.

At its core, this new case echoes these concerns—and the question that extends far beyond ophthalmology: When medicine becomes a business, what happens to patient care?

The allegations

According to the lawsuit, filed in Arizona, shortly after joining SEC in August 2023, Dr. Mayron observed patient safety issues, such as delays in treatment and inadequate staff training on critical safety protocols like “timeouts”.1

Timeouts are a standard surgical safety and other medical settings designed to ensure that the right patient receives the correct procedure at the appropriate site. Before beginning, the surgical team pauses to confirm key details, such as a patient’s identity and history, the procedure planned and any potential risks.

“We’re supposed to do timeouts, but most places don’t do that,” he explained during an exclusive interview with Media MICE. “[Doctors] cut corners, and then mistakes happen, unfortunately.”

The legal complaint asserts that Dr. Mayron attempted to train SEC staff and improve safety protocols, but he “received some pushback from staff and practice management.”1

Additionally, Dr. Mayron’s lawsuit details three specific cases of alleged negligence:

- Patient #1 experienced delays in receiving Avastin treatment due to prior authorization issues as staff were not “trained to get the appropriate and necessary authorization.”1

- Patient #2 suffered permanent vision loss after another SEC doctor “failed to note changes to Patient #2’s condition…and missed a bleed shown in a macula image” taken months earlier.1

- Patient #3 went blind following “physician incompetency”. The involved individuals were later disciplined by the Arizona Board of Optometry for their actions.1

According to the lawsuit, when Dr. Mayron raised these concerns with his practice manager, AVP’s chief medical officer and AVP’s compliance department, the complaints were found to have “no quality issue.”1

His lawsuit further alleges that key emails regarding these incidents were removed from the company’s email system—an act that the complaint describes as an attempt by the defendants to “cover-up the situation by deleting important records documenting the negligence which affected the review by internal compliance bodies and public licensing institutions.”1

The consequences

On April 26, 2024, Dr. Mayron was terminated from SEC, with the company citing “inappropriate behavior” and failure to align with company values.1

However, his lawsuit contends that the termination was classified as “without cause” and that he was entitled to a 120-day notice period, which was not honored. Dr. Mayron claims he was removed from the schedule, his patient appointments were canceled, and his health benefits were cut off—only reinstated after legal intervention.1

Dr. Mayron believes his firing was retaliation for speaking out. He describes a culture where raising patient safety concerns is discouraged. “As a physician, if you report something, [management is] not really happy to hear from you. They find that you’re an annoyance,” he noted.

Dr. Mayron also emphasized that his legal fight isn’t about financial gain. As an AVP shareholder, he still has a financial stake in the company’s success. “It’s extremely expensive to litigate,” he added. “And then for what damages? Very little. The damage is to the patients, and the damage is to our profession.”

READ MORE: Vitamins for Macular Degeneration: Slowing the Progression

Dr. Mayron explained that, due to a non-disclosure agreement with the company, the only way he can speak out about what happened, hold SEC and AVP accountable, and hopefully create change, is through litigation.

“The point of this whole thing is to show what’s really going on behind the scenes, so that the public has access to this information,” he insisted. “There has to be transparency.”

Private equity in ophthalmology

While Dr. Mayron’s allegations highlight troubling aspects of private equity-backed healthcare, research presents a more complex picture.

A 2024 study by Singh et al. found that private equity acquisitions of retina practices led to a modest increase in the use of higher-priced anti-VEGF treatments, raising Medicare spending, but showed no significant impact on diagnostic imaging or patient care patterns.3

Meanwhile, a perspective article by Groothoff and Browning (2025) suggests that private equity consolidation can improve operations, enhance technology access and provide administrative support, potentially benefitting patient care.4

Still, Grath and Sternberg (2024) note that concerns remain about financial incentives influencing medical decision-making. Some critics argue that profit-driven structures may lead to cost-cutting measures that affect patient outcomes, while proponents claim they streamline services and expand access to care.5

Profits over patients?

Beyond his own experience, Dr. Mayron sees his case as emblematic of broader systemic issues in corporate-run medical practices, where financial considerations sometimes take precedence over patient care. He pointed to prior authorization delays as a key example.

“You see a patient with wet AMD, and you want to inject them immediately to save their vision. But [management] says you can’t—you need to get prior authorization, which can take 72 hours,” said Dr. Mayron. “By then, [the patient] could permanently lose vision.”

READ MORE: The Art of Collaboration in Eye Care: Can Shared Expertise Lead to Better Vision?

He noted that some doctors in these situations will provide free samples of anti-VEGF medication to avoid delays. Dr. Mayron is a proponent in using samples for immediate treatment of patients who cannot afford to wait for insurance approval—something he believes is necessary to prevent vision loss.

He raised concerns that financial structures could discourage the use of free samples, as physicians are unable to bill for them. “When you do a sample, you can’t bill for it. So that means you get zero. But when you bill with Avastin, you get a payment.”

Supporters of private equity-backed models argue that standardizing processes, such as requiring prior authorization, helps manage costs and prevent unnecessary treatments. They claim such oversight balances cost efficiency with quality care.5

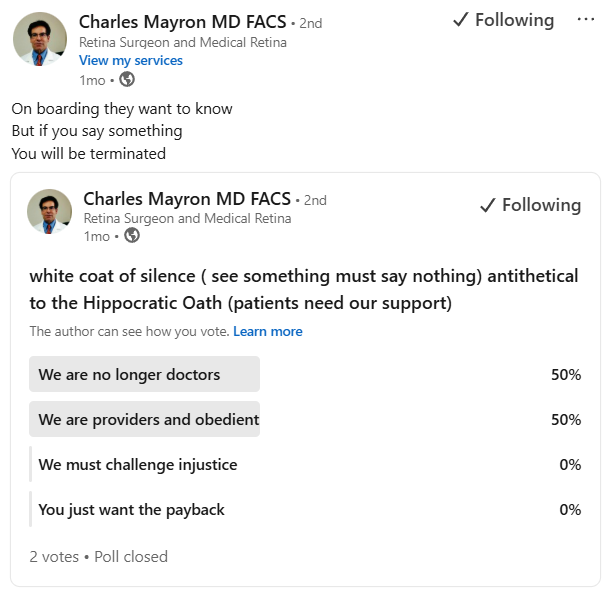

See something, say something?

Mistakes happen in medicine, Dr. Mayron acknowledged, but accountability is critical. “There’s an accountability of the provider or the system to make it right; to try to prevent it in the future.”

Physicians, he argues, have both a legal and ethical duty to report safety concerns—but many fear repercussions.

“We’re always supposed to ‘see something, say something’ and, hopefully, someone will do something,” he noted. “But I think people don’t want to cause waves because they might lose their job.”

Ultimately, he believes regulatory oversight is essential to prevent corporate interests from overshadowing patient care. “If there’s no oversight by the agencies to punish when companies do these things, they’ll just keep doing it.” he said. “Because in the end, it’s the bottom line. If their profits exceed their expenses, and they don’t get in trouble for anything, it’s a win for them.”

For now, Dr. Mayron’s lawsuit remains ongoing, adding to the broader conversation about the intersection of private equity and patient care. As the debate continues, this lawsuit serves as a focal point for discussions on transparency, accountability and the evolving dynamics of medical practice under financial oversight—and whether there’s room in the future for both.

Editor’s Note: American Vision Partners and their attorney was contacted for comment. As of publication, they have not provided a response.

References

- Mayron v. Southwestern Eye Center, American Vision Partners, Shaun Brierly. Superior Court of Arizona, Maricopa County. Case No. CV2025-004386.

- Matthews S, Roxas R. Private equity and its effect on patients: a window into the future. Int J Health Econ Manag. 2023;23(4):673-684. [Epub 2022 May 23]

- Singh Y, Aderman CM, Song Z, et al. Increases in Medicare spending and use after private equity acquisition of retina practices. Ophthalmol. 2024;131(2):P150-158.

- Groothoff JD, Browning DJ. Assessing private equity involvement in ophthalmology: Parallels with the past, concerns for the future. Am J Ophthalmol. 2025;270:245-251.

- Grath SL, Sternberg P. The unfolding story of private equity in ophthalmology. Ophthalmol. 2024;131(2):P159-160.