A hidden epidemic reveals ethnic gaps and missed opportunities in a high-performing health system

More than one-third of older Asian adults are living with an eye disease they’ve never been told about—an unsettling statistic for any clinician, and the central finding of a new JAMA Ophthalmology investigation.1 The study, involving nearly 1,900 adults in Singapore, suggests that undiagnosed age-related eye disease is far more common than expected in a country often held up as a model for accessible, high-quality care.

Striking undiagnosed rates in a high-income nation

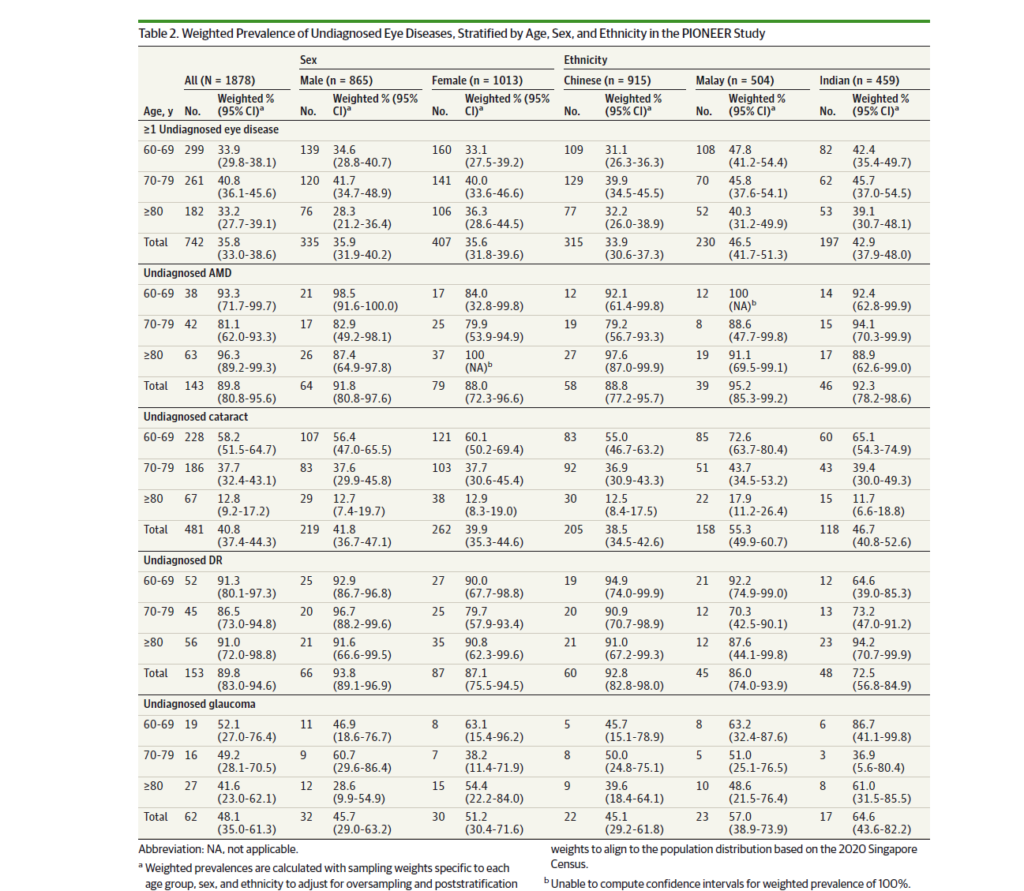

Researchers analyzed population data from 1,878 adults aged 60 and older across Chinese, Malay and Indian groups. They found that 35.8% had at least one undiagnosed condition, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), glaucoma or visually significant cataract.1

READ MORE: Advancing Eye Care Series: Exploring Dry AMD and GA with Dr. Carolyn Majcher

In an accompanying invited commentary,2 the authors noted that “although Singapore has a reputation for having a comprehensive, universal health care system, they found alarmingly high rates of undiagnosed eye disease; more than one-third (35.8%) of participants had at least one undiagnosed eye disease, with nearly 90% of AMD and DR cases going undetected.”

The findings mirror patterns reported more than a decade ago in the SEED cohort,3 suggesting that under-detection in this population is not new. That it persists within a high-performing health system raises questions about who is missing out on care and why.

The diseases that slip through the cracks

Across all four conditions studied, early stages often produce few or no symptoms. AMD was among the most frequently missed, with nearly 90% of cases undiagnosed across all ethnic groups. Early AMD is subtle on symptoms alone, making imaging vital for detection.1

A similar near-90% pattern held for DR despite Singapore’s strong chronic disease infrastructure. Many of these cases surfaced only through fundus imaging at the study visit, showing that early retinal changes continue to go unnoticed even among adults receiving routine diabetes care.1

Glaucoma went undetected in about half of affected participants, consistent with its reputation as a slow, quiet threat. Cataract fared somewhat better, though more than 40% of cases still went unnoticed. Gradual visual decline was often normalized as typical aging rather than recognized as correctable impairment.1

Collectively, these conditions behave less like isolated problems and more like a slowly rising tide, reshaping vision year by year unless someone goes actively looking for it.

READ MORE: Shedding Light on Dry AMD with eye-light® LM™ LLLT

Who carries the greatest burden?

The study found that Malay and Indian adults had significantly higher odds of having undiagnosed eye disease than Chinese adults, even after accounting for socioeconomic and clinical variables.1 As the commentary noted, “by illuminating ethnic disparities within a shared health care system, the study challenges assumptions about uniform risk and highlights the need for targeted, culturally sensitive interventions.”

Age added another twist. Adults in their early sixties were more likely to have undiagnosed disease than those in their seventies and eighties.1 Feeling relatively well may lead these younger seniors to skip routine screenings, giving early disease time to advance unnoticed.

READ MORE: Innovations in Retinal Imaging Benefit Glaucoma Management

The cost of undiagnosed disease

Beyond prevalence alone, the investigation measured the economic and quality-of-life impact of missed diagnoses. Older adults with undiagnosed eye disease had significantly higher healthcare expenditures, reflecting the compounding effects of delayed intervention. The study found that individuals with undiagnosed disease incurred 1.73-fold higher health care costs than those with diagnosed conditions,1 suggesting that early detection may yield economic benefits in addition to clinical ones.

They also reported lower scores on both general health (EQ-5D-5L) and vision-specific functioning (B-IVI), indicating meaningful reductions in daily capability. While falls were measured, they did not differ significantly between undiagnosed and disease-free participants after multivariable adjustment. Instead, the most consistent burdens were emotional strain, reduced independence and increased reliance on informal care.1

These findings show that the cost of missed disease is not limited to late-stage vision loss. It shapes everyday life long before patients reach the point of clinical urgency.

READ MORE: Posterior Segment Complications of Cataract Surgery

How Singapore can close the gap

The authors and commentators both point toward solutions that are practical, targeted and already within reach. Screening pathways need to meet people where they are. Workplace programs may capture the younger end of the 60+ population who are still employed. Community and neighborhood screenings can support older adults who may prefer familiar surroundings. Multilingual education campaigns can reduce uncertainty and help build trust in preventive care.1,2

Optometrists can widen access to first-line examinations without adding pressure to tertiary eye centers, especially in communities where under-detection is most common. Better coordination between primary care, optometry and ophthalmology could help close the loop so early findings do not vanish between appointments.1,2

Together, these strategies could help shift early disease from silent drift to early interception.

READ MORE: Advances in AMD and DME Take Center Stage at APAO 2025

A wake up call for aging societies

The JAMA study is not just a snapshot of Singapore. It reflects a pattern that other aging nations will face as populations grow older, chronic disease rises and early visual symptoms are normalized as part of aging. The persistence of under-detection across both SEED and this new cohort suggests that structural improvements alone are not enough to ensure timely diagnosis.

As populations age, the cost of undetected AMD, DR, glaucoma and cataract becomes harder to absorb. The next decade will test whether screening programs evolve quickly enough to catch disease earlier or whether these silent losses continue accumulating in the background.

Eye disease does not wait for symptoms, and neither should the systems built to find it.

Editor’s Note: This content is intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. It is not intended for the general public. Products or therapies discussed may not be registered or approved in all jurisdictions, including Singapore.

References

- Yee H, Wong CMJ, Gupta P, et al. Prevalence, risk determinants, and burden of undiagnosed age-related eye diseases among older Asian adults. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2025;ePub ahead of print.

- Wittenborn JS, VanNasdale D, Rein DB. Undiagnosed age-related eye disease in adults in Singapore. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2025;ePub ahead of print.

- Huang OS, Tay WT, Ong PG, et al. Prevalence and determinants of undiagnosed diabetic retinopathy and vision-threatening retinopathy in a multiethnic Asian cohort: The Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Diseases (SEED) study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(12):1614-1621.