You’d think living in near-total darkness for centuries would dull the Greenland shark’s vision. Apparently not.

A Greenland shark can retain healthy, functional vision for more than a century, according to a new study published in Nature Communications1, challenging the long-held assumption that eyesight is irrelevant in one of the darkest, coldest habitats on Earth.

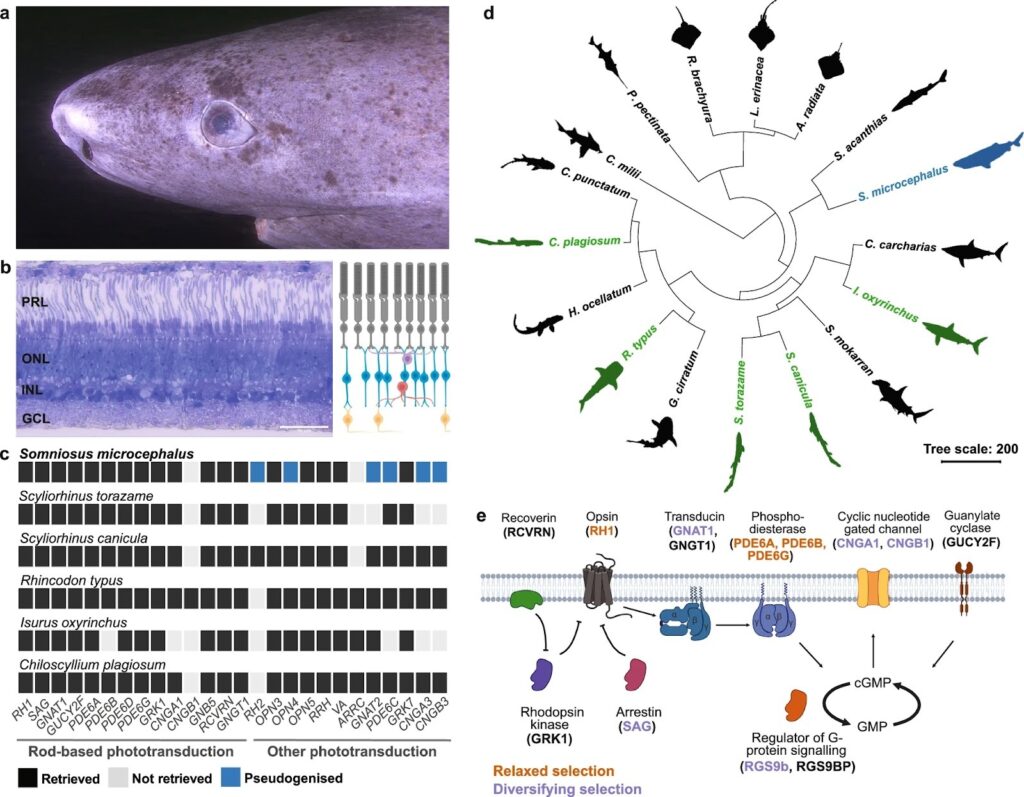

Drawing on genomic, transcriptomic, histological and functional analyses, University of California, Irvine (UCI) researchers found that the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) maintains an intact and highly specialized visual system even at extreme ages.1

Rather than deteriorating over time, the shark’s retina remains structurally sound and molecularly active1, offering rare insight into how neural tissue can endure across extraordinary lifespans.

Questioning a long-held assumption

Greenland sharks are the longest-living vertebrates known, with age estimates reaching up to 400 years. They inhabit cold, deep Arctic waters where light is scarce, and their corneas are frequently colonized by parasitic copepods. Together, these factors fueled decades of speculation that vision in the species was poor, degraded or largely unnecessary.1

READ MORE: Can a Retinal Implant Restore Vision in Dry AMD?

Behavioral observations began to complicate that view. Video footage showing Greenland sharks moving their eyes in response to light caught the attention of Dorota Skowronska-Krawczyk (USA), assistant professor of physiology and biophysics at UCI.

Her interest in the species traces back to a 2016 paper published in Science documented the Greenland shark’s extraordinary lifespan.2

“One of my takeaway conclusions from the Science paper was that many Greenland sharks have parasites attached to their eyes, which could impair their vision,” she said in a UCI news release. “Evolutionarily speaking, you don’t keep the organ that you don’t need. After watching many videos, I realized this animal is moving its eyeball toward the light.”

That realization led Skowronska-Krawczyk and colleagues to ask whether the shark’s visual system truly degenerates with age or has evolved mechanisms to remain functional for centuries.

READ MORE: Study Finds Comparable PCV Outcomes with Aflibercept 8 mg at Longer Intervals

Examining some of the oldest eyes on Earth

The researchers analyzed eye tissue collected between 2020 and 2024 from Greenland sharks caught near Disko Island (Greenland), in collaboration with teams from the University of Copenhagen and the University of Basel. Several specimens were estimated to be more than 100 years old, placing them among the oldest vertebrates ever examined for retinal health.1

Histological analysis showed that the shark’s retinas were fully intact. All major retinal layers were present and well organized, including the photoreceptor layer, inner and outer nuclear layers, and ganglion cell layer, with no obvious signs of thinning or degeneration.1

To assess whether subtle cell loss was occurring, the team performed TUNEL assays to detect DNA fragmentation associated with cell death. Even in very old specimens, the retinas showed no detectable evidence of ongoing cell loss, a notable contrast to the gradual retinal neuron decline observed in humans and most other vertebrates.1

READ MORE: More Than One-third of Older Asian Adults Have Undiagnosed Eye Disease, JAMA Study Shows

A retina built for darkness

The Greenland shark’s retina is structurally optimized for low-light environments. It is composed entirely of rod photoreceptors, which are specialized for detecting faint light. This rod-only architecture is common among deep-sea species and maximizes sensitivity in near-dark conditions.1

Genomic and transcriptomic analyses supported these findings. Genes required for rod-based phototransduction were intact and actively expressed, while most cone-associated genes involved in bright-light and color vision had been lost or rendered inactive over evolutionary time. The result is a visual system that is narrowly specialized but fully functional.1

Functional testing of the shark’s visual pigment added further support. When researchers expressed Greenland shark rhodopsin in the laboratory, they found it was strongly tuned to blue light, the wavelength that penetrates deepest in clear ocean water. This blue-shifted sensitivity is consistent with adaptations seen in other deep-sea species and is particularly pronounced in animals living at high latitudes, where blue light dominates limited ambient illumination.1

Seeing past the parasites

Corneal parasitism has long been cited as evidence against meaningful vision in Greenland sharks. To assess its optical impact, the researchers measured light transmission through parasitized shark corneas and compared it with human corneas.1

Although transmission varied, Greenland shark corneas, including those with parasites attached, still allowed substantial amounts of light to reach the retina, particularly in the blue-light range relevant to rhodopsin sensitivity. The parasites, the study found, do not render the eye functionally blind.1

READ MORE: Study Finds Shifting ROP Burden as Neonatal Survival Improves

DNA repair and visual longevity

At the molecular level, the team identified robust expression of genes involved in DNA repair within the shark retina, including components of the ERCC1-XPF pathway. In other species, this pathway protects against age-related retinal degeneration, and defects are linked to premature vision loss in humans.1

The elevated expression of these repair genes suggests that Greenland sharks may actively counteract the cellular damage that typically accumulates with age. While the study does not establish direct causation, it adds to growing evidence from other long-lived species that enhanced maintenance and repair mechanisms are central to preserving tissue function over time.1

Implications beyond the deep sea

The researchers caution against overextending the findings. Greenland sharks are not models for reversing aging, and their biology cannot be directly translated to humans. Still, the study provides a striking example of long-term neural preservation and highlights molecular pathways that may warrant further investigation in age-related eye disease.1

Studying a rare, long-lived species presents limitations, including small sample sizes and logistical challenges. Even so, the convergence of anatomical, molecular and functional evidence is compelling. The Greenland shark has not abandoned vision in the dark. It has adapted and preserved it.

Editor’s Note: This content is intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. It is not intended for the general public. Products or therapies discussed may not be registered or approved in all jurisdictions, including Singapore.

References

- Fogg LG, Tom E, Policarpo M, et al. The visual system of the longest-living vertebrate, the Greenland shark. Nature Communications. 2026;17:39.

- Nielsen J, Hedeholm RB, Heinemeier J, et al. Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus). Science. 2016;353(6300):702-704.