Among all patients treated in the field of ophthalmology, diabetic patients are some of those at the highest risk for a whole host of conditions. The dangers faced by diabetic patients are quite varied, and range throughout the eye.

For example, when a patient has diabetes, their chances of developing cataracts increase by 60%. Diabetics also have a 40% greater chance of developing glaucoma sometime during their lives.

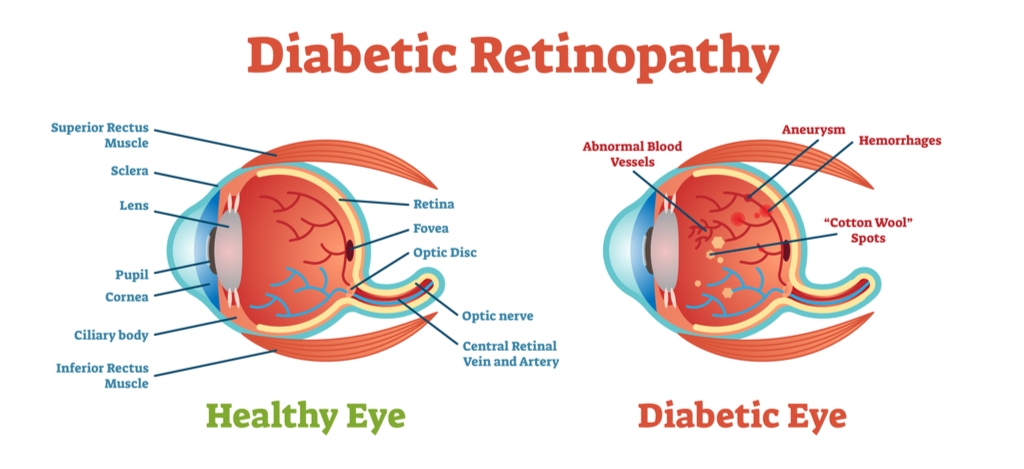

Most of the added dangers faced by diabetics, however, manifest in the retina. The basic and general term for vitreoretinal issues arising from diabetes is diabetic retinopathy. This condition underlies a number of further potential complications and comorbidities.

Many of these conditions affect the macula, the area at the center of the retina where the nerves responsible for visual acuity are most densely concentrated. In these cases, the condition is more specifically referred to as diabetic maculopathy.

One such complication of diabetic retinopathy — or more specifically diabetic maculopathy — is diabetic macular edema (DME). This condition is the most common cause of blindness related to diabetic retinopathy. It occurs when fluid accumulates in the macula, causing pressure and nerve damage. Most commonly, this edema occurs in cyst-like formations whereby it is referred to as diabetic cystoid macular edema.

Although it is the most common diabetes-related cause of visual loss, DME remains a fairly uncommon subject of discussion. In order to take a look at how this condition occurs, how it can be diagnosed, and what treatment options are available, it’s necessary to go over its underlying and overarching condition: that of diabetic retinopathy.

How Diabetes Mellitus Leads to Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetes mellitus — the broader term for several diseases that affect how the body handles and processes glucose — frequently results in a higher concentration of sugar in the blood. This blood sugar rise often accompanies a rise in blood pressure, and the two combined can cause damage to the arteries through which the blood flows.

In addition to the direct damage caused to blood vessels by the rise in blood sugar and blood pressure, in the more common form, known as nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, the increase in sugar can also cause blockages in the eye’s blood vessels. This in turn prompts the body to create new, abnormal vessels in the retina, in a more advanced condition known as proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy can cause leakage from these fragile vessels into the vitreous in the eye, as well as newly formed cavities in the retina and frequently the macula.

When this damage occurs within the retinal blood vessels, the delicate nerve tissue of the retina is also damaged. This damage, and any abnormalities that occur along with it, is the condition commonly referred to as diabetic retinopathy.

How Diabetic Retinopathy Leads to Complications, Including Cystoid Macular Edema

As mentioned before, diabetic retinopathy is accompanied by a wide array of complications. Often, these comorbidities give rise to greater risks to a patient’s vision than the underlying ocular condition. The prevalence of these diverse side effects are part of what makes diabetic retinopathy such a serious disease.

Some of these conditions are less serious than others. An example of this is that of a vitreous hemorrhage. Arising from both nonproliferative and proliferative diabetic retinopathy, this occurs when blood hemorrhages into the vitreous from the microaneurysms that arise from damaged or newly-formed blood vessels.

While troubling at first, this condition is not especially serious. The blood released into the vitreous is soon reabsorbed by the body on its own. While a vitreous hemorrhage can be severe enough to cause visual loss, this loss is temporary, and does not typically require treatment.

Retinal detachment is another comorbidity associated with diabetic retinopathy, one significantly more serious. It too can cause loss of vision, but it does not go away on its own. Retinal detachment frequently requires surgical treatment, including pars plana vitrectomy, repairs to the epiretinal membrane, intraretinal surgery, or increasingly, laser photocoagulation.

By far the most common of diabetic retinopathy’s comorbidities, however, is that of diabetic macular edema. When the capillaries in the eye are damaged or blocked, they can leak blood into the macula. There, the blood forms an edema: a buildup of fluid under pressure which creates a number of serious problems for the patient.

It is important to note that, while diabetic cystoid macular edema’s pathogenesis is always diabetic retinopathy, diabetic retinopathy does not always necessarily lead to diabetic macular edema. Other forms of macular edema can arise from conditions in patients who do not have diabetes, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), uveitis, or as a result of cataract surgery or glaucoma.

Thus, it is important to specify whether macular edema is diabetic or not. The terminology can become more confusing here as well, as diabetic macular edema is not always cystoid in nature. This is usually the case, as the diabetic macular edema, and that edema is usually of the cystoid variety.

Diagnosis of Diabetic Cystoid Macular Edema

It should go without saying that diabetic patients should undergo regular screenings for diabetic retinopathy and the many related conditions for which it is a precursor. Nevertheless, it never hurts to say it again, and to remind patients that regular diagnostic checkups are vital for diabetics and others with significant risk factors for eye diseases.

Among the detection methods which can provide clear and layered imaging is optical coherence tomography, commonly known as OCT. Optical coherence tomography allows for clear and layered imaging of the retina, the macula, and of its center, the fovea, the most concentrated locus of the eye’s photoreceptors.

Because of its increasing availability and advanced imaging capabilities, optical coherence tomography has become the preferred imaging method for many clinics and hospitals’ department of ophthalmology. As costs have come down, optical coherence tomography is making its way into many optometrists offices, and even patients’ homes as well.

Older imaging methods such as color fundus photography can also be of benefit in conducting an intraocular check-up. Fluorescein angiography is of considerable use in analyzing the blood flow within the retina. It is especially useful in identifying leakages within the retina’s capillary formations. Both of these methods involve the use of pigment within the eye in order to allow a clearer view of the eye’s inner workings, especially as blood vessels within the retina are concerned.

Risk Factors for Diabetic Cystoid Macular Edema

Patients who suffer from diabetic cystoid macular edema frequently — but don’t always — present symptoms consistent with their underlying diabetic retinopathy, such as blurred vision, dark spots or vision loss. Often, these patients experience a more specific loss of vision in the depth of field and color sensitivity, as well as metamorphopsia that can be demonstrated on Amsler grid, micropsia and central scotoma.

Diabetes mellitus is of course the defining risk factor for developing diabetic cystoid macular edema. Specifically within that, the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study identifies three specific characteristics for those at heightened risk for developing cystoid macular edema:

- Any retinal thickening within 500 μm of the foveal center

- Hard exudates within 500 μm of the foveal center that are associated with adjacent retinal thickening (which may lie more than 500 μm from the foveal center)

- An area of retinal thickening at least 1 disc area in size, any part of which is located within 1 disc area of the foveal center

In addition to these three guidelines, a number of other preconditions are well established as risk factors for developing diabetic cystoid macular edema. These are often abbreviated with the acronym DEPRIVENS:

- Diabetes

- Epinephrine: Treatment with epinephrine drops has been shown to double the likelihood of developing diabetic macular edema

- Pars planitis or uveitis

- Retinitis pigmentosa

- Irvine Glass: A complication arising from cataract surgery

- Vein occlusion

- E2-prostaglandin, which can cause constriction of capillaries

- Nicotinic acid and niacin (in doses greater than 1.5mg/day)

- Surgery, particularly pars plana vitrectomy, laser photocoagulation, cryopexy and various glaucoma procedures

Treatment Options for Diabetic Cystoid Macular Edema

Several steps are usually involved in treating diabetic macular edema. The first of these is to prescribe a non-invasive steroid medication in order to alleviate swelling. Dexamethasone and triamcinolone acetonide are frequently prescribed as drops, or occasionally via intravitreal injection or ingested orally. Diuretics, such as acetazolamide (Diamox), have been shown to help to reduce inflammation in clinical trials as well.

Once the initial subretinal swelling has subsided, doctors frequently prescribe treatments to inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) drugs such as bevacizumab or ranibizumab. These drugs are designed to inhibit the systemic growth of new blood vessels that can cause damage in the first place. These drugs are always administered by intravitreal injection, and have shown remarkable improvements in patients’ vision.

Once these two pharmacological treatments are performed, doctors will frequently perform one or both of two options to treat the cystoid macular edema itself. Increasingly, ophthalmologists are opting to perform laser therapy to eliminate the macular edema. This has shown a relatively high success rate, and has been shown to eliminate the edema with minimal damage to the foveal surface.

Another option frequently explored is the pars plana vitrectomy. This procedure is performed when doctors have identified a higher degree of vitreomacular traction than usual, a significant breach in the blood-retinal barrier, or other intrusions into the eye’s vitreous that may have caused contamination therein.

In Conclusion…

While treatment is available for diabetic cystoid macular edema, it is imperative that this treatment take place before the loss of vision takes place, and not after. Often, once the Müller cells — those which receive and transmit images to the brain — have been damaged, they cannot be repaired.

Thus, while visual loss due to DME is preventable, it is not reversible. This makes patient education and early screening the first priority in addressing this condition.